Victoria Smalls is a triumph of human unity.

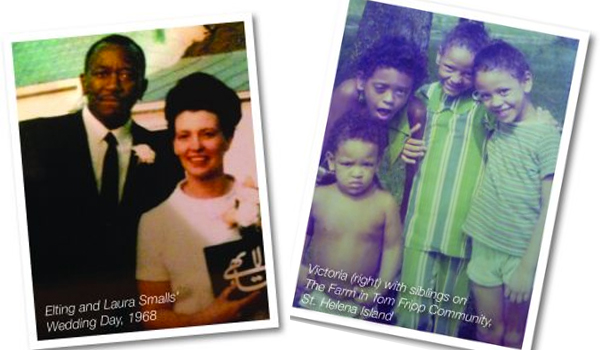

She is Gullah, one of 14 siblings in the blended family of St. Helena Island’s first-ever biracial couple. She grew up speaking Gullah and working the land; today she is a director at Penn Center National Historic Landmark District, a successful artist and a mother raising the next generation. Victoria is a living part of history.

Her own story began at an interesting time. The year was 1966. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had just spoken at Penn Center, when another crucial meeting took place.

“My mother saw this tall, charismatic, beautifully dark-skinned man standing 6’6”,” says Victoria, one of four children born from their union. “They started officially courting, then decided to get married.” He was Gullah and a graduate of Penn Center with six kids from a previous marriage, all black; she lived in Michigan with four kids from her own previous marriage, all white. Both their spouses had passed away. Amazingly, both were also members of the Baha’i Faith, a world religion founded in Iran that emphasizes the unity of all humankind under one God. It was at a Baha’i retreat on the grounds of Penn Center that they met.

When Victoria’s mother came to St. Helena, almost the entire population was African American.

Yet, she and her children were fully embraced by the love of the community and, according to Victoria, the Baha’i Faith really helped. “That is my foundation on how I live my life,” she says, “how my community should be, where I want to work and my philosophy on unity within diversity. It’s just so beautiful, and I got that foundation from my parents.”

So, this huge colorful family grew up in the fairly idyllic environment of the Sea Islands, living off the bounty of land and water. All 14 cleaned fish and worked the fields together. At harvest time, their father took them around delivering extra corn or sweet potatoes to the elders, as is the Gullah way. But blended families can be difficult even without the race issue, so how did they maintain harmony?

“That’s always the question,” Victoria acknowledges. “At a time when segregation was going on, not only officially but also in the comfort levels of the community, how did we all get along? And the answer is, it was us against them: kids against the parents! You know, like the Brady Bunch—that was our frame of reference at the time.”

In those days, Victoria spoke Gullah like all her friends and neighbors.

She didn’t know it was another language; that was just the way they talked. But, by age nine, she began to notice that whenever they went into Beaufort—only seven miles away, yet somehow culturally distinct—when she opened her mouth, people laughed at her.

“I started not wanting to speak in public,” she remembers. “I was loud because I came from the country and the fields, but I became quiet because I was made to feel ignorant and ashamed. Everything that came out of my mouth was Gullah, which to others meant ‘those enslaved people.’ Speaking Gullah, being Gullah, was not fashionable at that time. Now it’s a household name.”

In response to this humiliation, young Victoria started watching the nightly news and mimicking Walter Cronkite to develop new speech patterns all on her own. This tactic worked—but initially it also gave her a stutter. Only within the last year has she realized exactly why that happened: in the Gullah language, words are cropped, final Rs are dropped, and the Th sound is replaced by D. For example, rather than saying them, that, there, she would say dem, dat, dere; rather than floor or door it was flo’ or do’. So, as Victoria worked to retrain her speech, every time she tried to say words such as these she stuttered. “It was a battle,” she recollects. “That Gullah girl wanted to come out, and suppressing her turned into a lot of pain.”

While it felt like an eternity of struggle, she only stuttered for perhaps four or five years.

The turning point came one day at the post office when she ran into a local root doctor (witch doctor) who inquired about her family. Listening patiently as she stumbled over the words, at last he said gently, “You know I can help with that.” Aware of his occupation, Victoria panicked, thinking he would put a spell on her; yet his smile was so kind, and her upbringing of respect to elders won out. “Yes, Mr. Gregory,” she replied. But all he told her was, “Think about what you’re going to say before you say it. Then sing your words.”

It was golden advice to last a lifetime. By the time she left for South Carolina State University, both the stutter and the rich Gullah accent were gone. Today, she speaks eloquently in a clear ringing voice that betrays no particular origin. However, this is a both a blessing and tragedy to Victoria.

“It’s not effortless for me to speak the Gullah language now,” she says, adding that she hopes reading De Nyew Testament in her native tongue might help restore her fluency. “To some people, Gullah might sound like you’re just murderin’ the English language; but what many don’t realize is there are about 5,000 West African tribal words in Gullah—so it is a Creole language, a blended language. Had we known it was going to be lost, we as a community would have done more to preserve it.”

This delving deep into her roots goes far beyond the language.

Working as Director of Development for the Penn Center is a way for Victoria to not only stay in close touch with her heritage, but share the wealth of it with others. “Being Gullah means you have kept most of your Africanisms alive,” she says. “That includes the traditions, culture, food ways, spiritual practices, maybe even supernatural beliefs. And the Sea Islands have been incubators with their communal family setting like a village in Africa. So, I feel a great sense of purpose at Penn Center because our mission is to promote and preserve the history and culture of the Sea Islands.”

Most recently, Victoria was appointed to serve South Carolina as a Commissioner of the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor. “That little Gullah girl who was stumbling over dem, dat, dere,” she says, “now she gets to speak on one of the highest levels of our nation about this culture’s significance so it doesn’t become extinct. I mean I have goosebumps right now—there are just no words to express how it feels to be able to serve in this capacity.”

Although she lives on St. Helena, these days Victoria is liable to be seen around Bluffton. She has family here and feels a strong Gullah presence. Moreover, since becoming involved with the vibrant art studio/gallery Bluffton Boundary, it has become her home away from home. She comes here to create, learn, and share her expressions with others.

“Fifteen years ago, I started painting faces that represented the hues of my family,” said Victoria.

She works in pastel using her fingers to directly transfer feelings and prayers onto paper. “The beautiful darks and browns of my father’s family, the peach tones of my mother’s, and all the colors in between. But I would paint them with their eyes closed because I was going through a tough time and wanted to surround myself with the serenity of a peaceful, meditative state.”

Although she originally just used the faces to decorate her own home, Victoria soon had so many she started selling them on consignment at St. Helena’s landmark gallery, The Red Piano Too. “I forgot all about them until I started getting checks in the mail,” she said. She was astonished when her work sold out completely and the owner, Gullah art maven Mary Mack, personally requested more. Not long after, Victoria started working at the Red Piano—curating exhibits, learning fine framing, and getting to know the artists on an individual level—which resulted in what she calls “the most perfect arts education.” Simply being surrounded by people who expressed their love for all things Gullah through fine arts, outsider art and crafts like sweetgrass baskets was, for Victoria, “like falling in love all over again through the artwork of our people.”

Her studio at Bluffton Boundary gives her a special space in which to create.

It also provides the opportunity to interact with the community, in particular the youth who come for classes. She also feels fortunate to be taken under the wing of successful Bluffton artist Amiri Farris. Though right now she still mostly paints her signature faces, the words of a Gullah art icon ring in her mind: “Jonathan Green says ‘Paint what you see.’ I have a few pieces of the Gullah community, but I think I’m ready to start doing more of that.”

Victoria began using pastels since that’s what her mother worked in, and now she’s passing the torch on to her own children. Her 24-year-old son is a fine artist and metalsmith in Charlotte, and her 11-year-old daughter also paints. For Victoria, losing her 17-year-old son was yet another reason creating became such a healing release. There is so much to her story, too much to cover here, plus what’s yet to be written. But anyone who’s interested can talk to her personally at Bluffton Boundary! She welcomes people just as she has been welcomed by them.

“I really love Bluffton,” says Victoria. “This place is special, and the commute is not a problem because the drive is therapeutic for me. It truly is a second home.”

Penn Center: Past, Present & Future

On January 12, 2017, President Obama declared the Penn Center on St. Helena Island a National Monument recognizing its pivotal role during Reconstruction. This timeline highlights a few important dates in Penn Center’s legacy and its current mission “to promote and preserve the history and culture of the Sea Islands.” For more information, visit penncenter.com.

- 1862 • First school for freed slaves established on St. Helena Island, South Carolina; classes held at The Brick Church; 80 pupils enrolled.

- 1865 • New three-room building becomes first school in the South created for the instruction of former slaves; officially named Penn School. (Thirteenth Amendment added to the U.S. Constitution; slavery legally abolished.)

- 1865-1877 • School supported by private charity comprised of primarily Quaker abolitionists in Philadelphia.

- 1901-1917 • Hampton Institute in Virginia asked to sponsor Penn School; Center’s new leadership modeled education on Hampton Tuskegee model.

- 1927 • Completion of bridge from town of Beaufort to Lady’s Island gave St. Helena access to the mainland.

- 1948 • Penn School ceased to function as a school; changed to a community agency; renamed Penn Community Services, Inc.

- 1950 • Penn School becomes Penn Center.

- 1960s • Sponsored and hosted interracial conferences on Civil Rights; Penn Center is a retreat site for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and human rights activists.

- 1980s • Penn Center established Land Use and Environmental Education (LUEE) Program to promote sustainability and economic development; creation of Penn School for Preservation.

- 1990 • Penn Center placed on “most endangered historic places” list by the National Trust for Historic Preservation; mission focused on promoting and preserving Gullah cultural assets.

- 2006 • Congress created The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor along the coast from Florida to North Carolina.

Article written by Michele Roldán-Shaw.