My Journey: The Art of Bluffton

The human hand could hardly paint a finer scene than what appears around every bend in the Lowcountry. Natural beauty is certainly the first quality here to recommend itself to the artist—professional or hobbyist, native or newcomer, visitor or resident—and second is the thriving arts scene wherein they find support and a market for their work.

But there is another, less obvious factor, one that might only be experienced by the individual who has made art more than a trade or a hobby, but an entire way of life. And that is the love shown in the Lowcountry for free spirits, coupled with a willingness to help them fly.

I came to Bluffton from the West Coast at age 21 with a one-way ticket and a duffel bag. I knew nothing about the area and very little about myself. Although I had drawn and painted my whole life, and later began writing, it wasn’t until I came here that I really blossomed in these fields.

Back then, Bluffton was still sleepy; new growth sprouted along the Highway 278 corridor.

But Old Town was a languid dream. On Calhoun Street, snakes lurked in overgrown lots, and owls hooted in the daytime; buzzing insects drowned out the sound of cars; grizzled loafers on bicycles outnumbered the tourists. I used to just stand on the yellow line as long as I felt like it. It was the ideal climate for folk art.

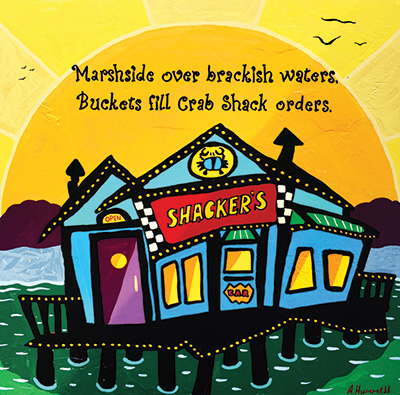

The first time I ever set foot in Old Town, I wandered into what was then Amos Hummell’s studio gallery on Calhoun Street. Amos had been painting bright, iconic Lowcountry art for years, and his workspace looked like the scene of an all-out paintball gun war with teams for every color of the rainbow—everything was splattered, including Amos. His personality was equally colorful. I felt instantly at home. We struck up a conversation and he kindly offered the use of supplies, saying I could just “throw $10 in the pot,” so I created my first piece of artwork on the spot (a gift for my mom).

Later, he would tell a newspaper reporter that it was like giving food to a stray. I spent the next several years working out of his studio on off-days from my other lines of work, and I am indebted to him for the start of my local art career. It was Amos who taught me the ways of latex house paint on particle board (very affordable materials), generously training me to cut, sand, prime, paint and fit the boards for hanging. I doubt he would remember it that way; our friendship was the basis for informal instruction and so much more.

I sold my first piece for $30 when two ladies from California bought the papaya I painted on a wood scrap out of Amos’ dumpster.

Several years later, I did a mural on Hilton Head for $3,000. That was, perhaps, the peak of my career.

For the most part, I have been the quintessential “starving artist,” surviving by my wits, work ethic and the kindness of friends and strangers. Whether tramping the marsh in search of driftwood boards on which to paint “It’s 5 o’clock somewhere,” hustling pet portrait commissions or hauling thrift store furniture to decorate and sell at Mayfest, I have really scrapped.

My survival has hinged on the fact that people here support not only art, but the artists themselves; not only the enjoyment of art, but the pursuit of artful living. For those of us who dedicate our lives to art, we often—though not always—find ourselves obliged to forsake certain comforts and securities that more stable, lucrative professions provide. We choose to take a different path, or perhaps it’s simply fated. We require a community that appreciates the different drumbeat we march to.

Bluffton has been such a place for me.

I have clients who have bought or commissioned dozens of paintings; friends who have donated supplies or hired me to give art lessons to their children; benefactors who have fed and sheltered me for years during rough patches. I feel so grateful toward all those who encourage, inspire, sustain, nurture and cast their vote of confidence in me, which is essential to the artist’s spirit—if nobody cares what we’re doing, there’s little reason to persevere.

People in Bluffton care. They applaud living imaginatively. The South in general reveres its primitive, outsider, visionary, self-taught and folk artists, those mad-hatters who follow inner muses with no training or regard for convention, who paint with mud in their swamp-shacks or transpose urgent visions from God or cover everything they own with polka dots.

It’s as much about their story as it is about the tangible objects they create. Through them, one’s mind expands to encompass other, freer modes of living. So, with Bluffton’s long and proud identity as a town of eccentrics, quite naturally art and artists thrive here.

Creative Blufftonians

Nancy Golson,

owner of the shop Eggs ‘N’ Tricities on Calhoun Street, has long been a purveyor and benefactress of local art, and her shop features the work of her daughter, Margaret Golson Pearman, a talented artist in her own right.

“People love to hear my story,” said Margaret. She paints lively expressions of local fixtures like blue crabs, sea turtles and shrimp boats. “I’m from Bluffton, I grew up on the river and my mom always supported me to do whatever I wanted creatively. Plus, I have a stake in what happens here, so the money they give me goes back into the community.”

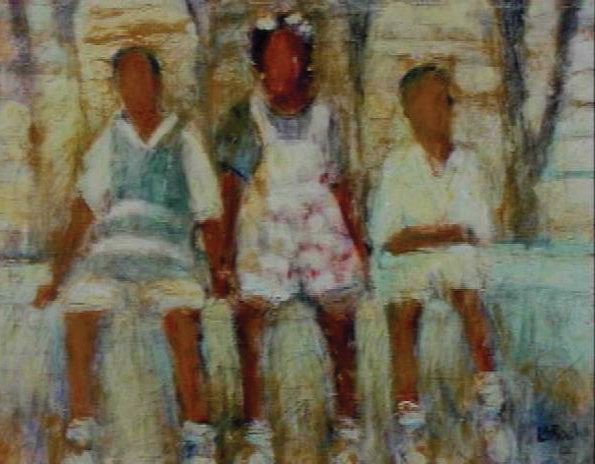

Louanne LaRoche,

a key figure in the fine arts scene, is known for her evocative renderings of Lowcountry flora, fauna and culture, but also for bringing out the work of others—in particular, the celebrated outsider artist Sam Doyle. Though now deceased, Doyle once filled his St. Helena Island yard with exuberant depictions of Gullah life painted on wood and tin scraps. Today, his work is some of the most valuable, recognizable and highly collectible of any American folk artist.

“Bluffton has a history of being a sanctuary,” said Louanne, who works from her home studio on the May River and shows at Four Corners Gallery. “I think it attracts those people who want to bring out their inner eccentric, but haven’t given themselves permission to do so. So, to be around those who are freer—not in a showoff way, but that’s just who they are—it helps people become brave.”

Two brave personalities in the local art scene are Pierce and Pressly Giltner,

who exude the creative spirit. She’s a photographer, and he’s a painter and builder of rustic art installations. Originally from Chester, South Carolina, they spent time living in a primitive forest cabin. Later, they came to Bluffton and integrated themselves into the community with enthusiasm.

“It’s easier to be yourself here,” said Pressly, who brings energy to her documentation of local life in photos. “If you’re a little offbeat, people embrace that. If you’re doing something awesome, they love it! They want to hear all about it.”

In addition to her own projects, Pressly has worked with her husband Pierce in a unique collaboration. It portrays the world of a local oysterman fondly known as “Drack.”

Their body of paintings and photographs that capture a classic slice of Bluffton. Pierce’s ultimate vision for the project is to produce a major show featuring both his paintings and Pressly’s photographs. They wish to take Drack on the road with him to Charlotte, Charleston and New York.

“I think we’re surrounded by extremely talented, but underrated artists,” said Pierce. “People should wake up and smell the roses as far as the incredible work that is being done in Bluffton.”

By Michele Roldán-Shaw